Feb 25, 2015

Vilan van de Loo

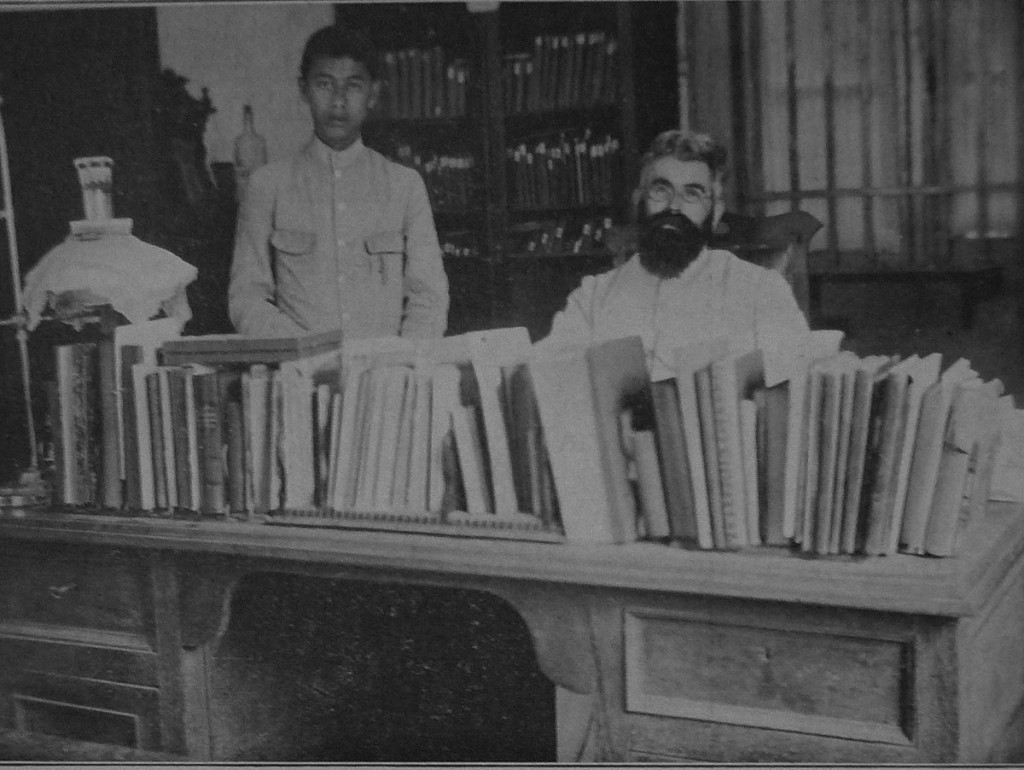

At the end of 1892, two men knelt in a cabin of the boat, “The Conrad.” Gerard Veldhuyzen, Jr. prayed for the safety of his friend Johannes van der Steur (1865-1945), who was about to leave the Netherlands for the Dutch East Indies. Veldhuyzen knew his friend too well to be able to trust in a peaceful future. Van der Steur was stubborn, and too ambitious to compromise on anything. He had never been in the colony, yet planned to live and work there among the K.N.I.L. (Dutch Colonial Army). After months of fundraising Van der Steur had been consecrated in the church at the Parkweg in Haarlem. He was ready to go.

It seems that hardly anyone in the Indies was happy with the arrival of Van der Steur. The press mocked his beliefs and his personality. He was a well known man thanks to his involvement in the anti-prostitution movement. Yet Van der Steur succeeded. He opened

in Magelang (Java) a military home called “Oranje Nassau.” Soldiers in the colony often lived isolated lives. Van der Steur offered them a brotherly love in a Christian environment.

Early in 1893, one of his visitors informed Van der Steur about four children in the kampong, whose Italian father had died. Instead of looking for their relatives, Van der Steur adopted the children. Soon after this a mother came to him asking for medicine for her children. He supplied that, but within a few days he took her children in his home as well. It was a typical colonial way of acting; the European civilization was considered to be superior, the indigenous were regarded inferior. One believed that every child with a European father had the “right” to be part of the European civilization.

More and more children followed, some brought by their (last remaining) parent, others in need of a home. Within a year the life of a single father became too much for Van der Steur. He wrote a letter to the Netherlands, asking his mother to come and help him. It was not she who arrived, but Marie van der Steur (1868-1962), his sister.

Conflicts

When Marie arrived in Magelang, the children immediately loved her. The young woman (then 24) loved them too. Even though everything in the tropics was strange to her, she quickly found her way, adapting to the customs, the food, and even the long hours working in the heat. A woman’s work was never done here and Marie was a working woman. For the military men, she was the sister they all wanted to have, to the children she was a mother; her brother found in her his confidant. Very soon, she was the head of the girls department.

Marie had arrived just in time, as Van der Steur was having conflicts with the local authorities. They wanted the children at school or at work on Saturdays. For Van der Steur this was the Holy Sabbath. Eventually the matter was solved through intervention from the Netherlands. But this and similar conflicts must have had him reconsidering his position.

In the Netherlands, the Seventh Day Baptists fully supported the Van der Steurs, but only within their means. There was not as much money as Van der Steur needed. Their range of publicity — mostly in their own magazine De Boodschapper (The Messenger) — was small. Even though Van der Steur managed to get his fundraising articles published in more Christian magazines, it did not help much. A dominant factor in this was the mistrust he faced being a Seventh Day Baptist. When people asked questions, he refused to answer, stating his beliefs were a private matter. That obviously did not help.

Around 1895 he must have chosen ambition and money above remaining loyal to the church that had nurtured him so dearly. Van der Steur broke his ties with Seventh Day Baptists and started his own magazine, now profiling him self as a “Christian man.” In doing so he was able to expand his fundraising and ask every Christian for donations. That worked well. During the course of his work he raised enough money to care for around 7,000 children and take care of an unknown number of soldiers. He had many helpers, male and female, but he was and always remained the main man.

Intentions

The life and work of John van der Steur is fascinating. It is a tale of colonialism, filled with good intentions from the European point of view. Yet one wonders what the Indonesian relatives would have thought about “disappearing” children. That story still has to be told.

Vilan van de Loo was a Dutch independent researcher from the Netherlands. Her interests are history and literature. Her biography of John van der Steur will be published May 2015 (in Dutch). Contact? Mail: vilan@xs4all.nl